Berlin, Germany, 30 May 2024 – In late May 2024, Berlin welcomed a group of eight young human rights activists from across Indonesia. Their week-long visit was to understand and explore the nuances of remembrance culture in Germany, while building connections beyond national borders.

Their journey to Berlin was the culmination of a two-year collaboration between Asia Justice and Rights (AJAR) in Indonesia and Watch! Indonesia in Germany – a project aimed to strengthen young activists by providing expertise and knowledge, while fostering international networking and exchange. These activists have all been working on initiatives to preserve the memory of human rights violations in Indonesia.

During their time in Berlin from 21-28 May 2024, they learned from Germany’s memorials, museums, and educational initiatives, which have played a crucial role in shaping public discourse about the Holocaust and other atrocities. By engaging with German civil society organisations, they also gained valuable insights into how to advocate for accountability and justice in their own context.

On their first day, AJAR and the eight learning exchange participants visited the museum and Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, located near Germany’s national monument, the Brandenburg Gate. Adam Kerpel-Fronius from the Foundation explained that this memorial is the main commemoration of the Holocaust, in which over 6 million jews from across Europe were murdered by the Nazi regime. Adam also explained how efforts to acknowledge and prosecute all perpetrators were hindered after World War Two, yet despite the obstacles the memorial was established through the combined efforts of survivor communities, activists, academics, and Jewish religious groups.

The second site visited was the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma, located to the side of the Brandenburg Gate and across from German Parliament. Its design, featuring a dark pool with flowers that are regularly replaced and positioned in the centre of an altar, mirrors the parliament building itself, symbolising the German government’s involvement in the dark history that victimised not only Jews, but also other marginalised minority groups including the Sinti and Roma, people with physical and mental disabilities, or those with different gender expressions. The memorial’s design, which is integrated with nature, was a request from the Sinti and Roma community.

While the memorial acknowledges the state’s responsibility in mass human rights violations, its future is uncertain due to planned construction in the area. This raises questions about the government’s commitment to reparation and the memorial’s role in satisfying victims’ demands for recognition and justice. Reflecting on her own experiences in state-involved memorialisation in Rumoh Geudong, Aceh and the need for a victim-centred approach, Ihma from PASKA Aceh, noted, “memorialisation exists because there were victims. Regarding memorialisation initiatives, the victims’ meaningful participation became a central foundation to consider in building an ethical memorial and respecting the victims’ life stories.”

The group continued to two other memorials: the House of the Wannsee Conference – a memorial and museum housed in a villa near Berlin, and the Topography of Terror, located on the former site of the SS headquarters. The House serves as a stark reminder of the systematic nature of the Nazi’s mass murder. The villa was where high-ranking Nazi officials met to discuss the “Final Solution”. The museum exhibits artefacts and documents that reveal the meticulous planning behind this genocide, emphasising the state-organised nature of the crimes.

The Topography of Terror offers a different perspective on Nazi atrocities; the perpetrators and the institutionalised terror they inflicted on various marginalised groups. The museum’s exhibits delve into the mechanisms of state-sponsored violence and serve as a reminder of the importance of understanding the root causes of violence and the role of institutions in perpetuating it. Both memorials play a crucial role in educating the public and ensuring that the horrors of the past are not forgotten. They stand as testaments to the ongoing efforts to grapple with Germany’s history and promote a culture of remembrance and responsibility.

While the human rights situation in Indonesia remains fraught and the government resists calls to address historical injustices, the visits to these memorials demonstrated that even in a country like Germany – which has had several decades of historical remembrance – upholding human rights and memorialisation is an ongoing struggle.

In the context of ongoing conflict, which makes such initiatives very challenging, Orideq from Perdamaian dan Keutuhan Ciptaan (KPKC) Sinode Gereja Kristen Injil (GKI) Tanah Papua noted, “Reflecting on my experience with my community in Papua, I believe that memorialisation initiatives should include honest and open truth-telling based on historical facts and documents. This ideal is still difficult to implement in my community, making it a long-term task that we need to address.”

During World War II, the Nazi regime established 23 concentration camps across Europe, notorious for their systematic persecution and extermination of millions of victims. Ravensbrück, the second largest after Auschwitz, specifically targeted women, including political prisoners and Jews, who resisted Nazi ideology or belonged to marginalised groups. The camp, once a place of unspeakable suffering, has been transformed into a memorial to honour those who perished. It highlights the dual narratives of female SS members’ active roles in torture and murder, and the tragic stories of victims subjected to forced labor and brutal executions.

The exhibitions at Ravensbrück underscore the significant but often overlooked role of women in Nazi atrocities. Many female perpetrators acted voluntarily, contributing to the camp’s horrors. Despite their active involvement, post-war justice systems largely ignored or inadequately prosecuted them. This historical neglect was compounded by gender biases that minimised women’s roles in the systematic crimes of the Nazi regime. The camp’s exhibits strive to rectify this narrative, illustrating how female guards and collaborators were complicit in crimes against humanity.

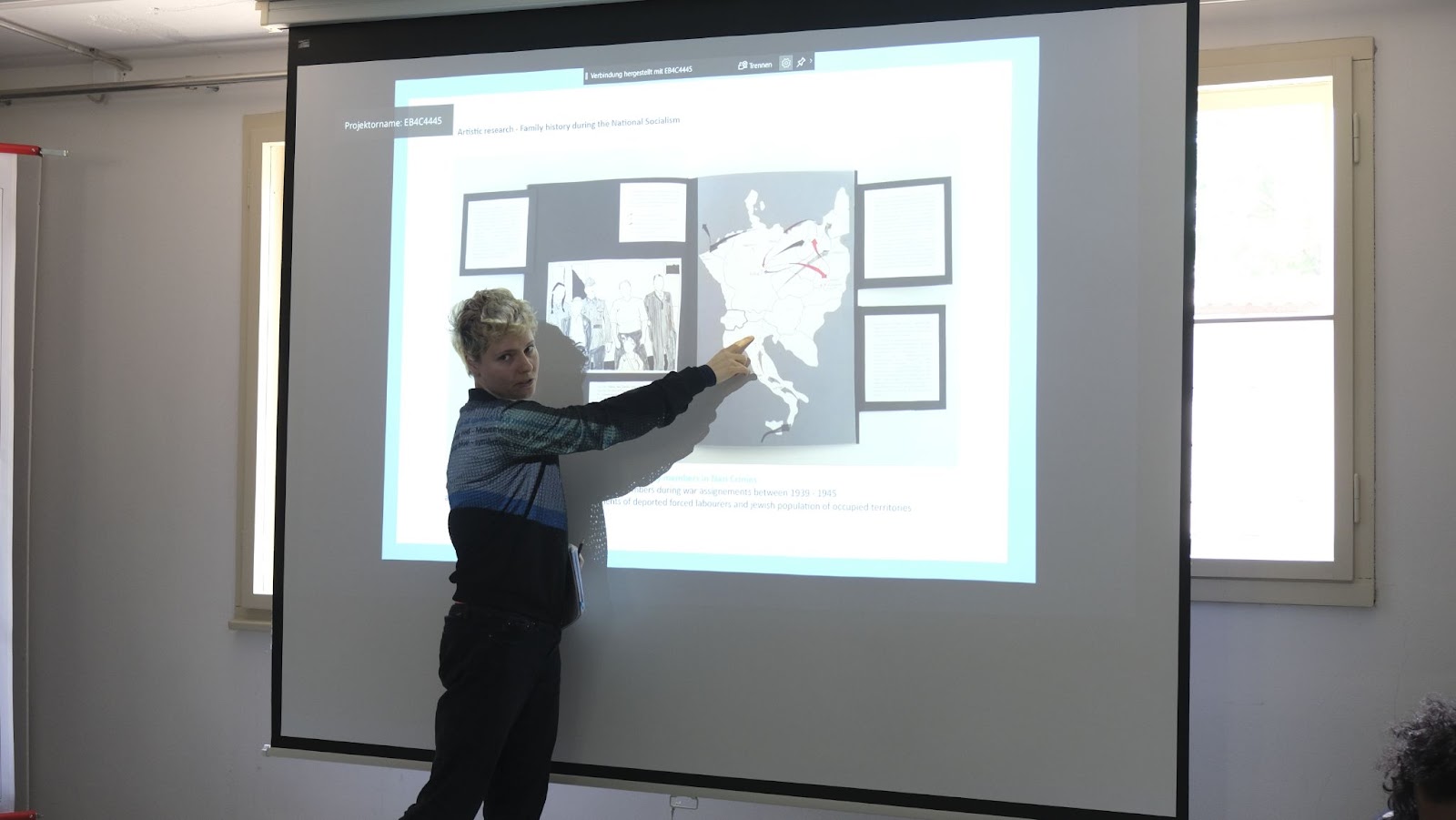

The group also visited the Nazi Forced Labor Documentation Center, followed that day by a reflective discussion with Maria Gleu to learn about the role of descendents of perpetrators in documenting past crimes. Maria has been involved in documenting the story of her great-grandfather – a member of the Nazi party – and explained the process of uncovering personal narratives while adhering to rigorous historical methodologies. She also outlined her personal approach to gathering information which involves casual conversations and eliciting stories by looking at albums together or engaging family members who might have connections to archives or artefacts.

In a separate workshop with Sophia Schmitz, participants learned about the concept of “history from below,” a grassroots-driven approach that focuses on personal narratives and community engagement, rather than solely on grand events or figures. This method, often used for advocacy, allows for a more inclusive and accessible understanding of history. This was specifically in relation to the Stolpersteine project, now the largest decentralised Holocaust memorial.

Stolpersteine, or stumbling stones, are small brass plaques embedded in sidewalks across Germany and Europe to commemorate victims of Nazi persecution. Initiated by Gunter Demnig, a descendant of a perpetrator, in 1992, this artistic intervention in public space sparked controversy due to its placement on the ground, where the names and details of victims could be stepped on. Despite initial criticism, this grassroots memorialization effort has gained acceptance over time, emphasising the importance of individual remembrance and collective participation.

As well as learning about Holocaust memorialisation, the participants also visited the Berlin Wall Memorial – a reminder of the Cold War division of Germany and the human rights violations that occurred along the border. The memorial, initiated by civil society and supported by the state, attracts millions of visitors annually. Its main focus is the ideological contestation of the Cold War and commemorates the victims killed trying to cross the Berlin Wall. Also focusing on this period, the group met with Juliane Thiene from the Leipzig Citizens’ Movement Archive which documents grassroots artefacts like music and art from the Cold War period. The archive’s emphasis on punk bands and their lyrics provides a unique perspective on the resistance movements within East Germany.

One the fourth day, the participants visited the “Buried Memories: Dealing with Remembrance. The Genocide of the Ovaherero and Nama” exhibition at the Neukölln Museum. Under the guidance of historian and archaeologist Dr. Matthias Henkel, the group engaged with the installation by Isabel Tueumun addressing the often-overlooked genocide of the Herero and Nama people in Namibia, committed during German colonial rule. Discussions with Dr. Henkel emphasised the interconnectedness of history, memory, and responsibility. The exhibition, while small in scale, has resonated with the African diaspora and sparked broader conversations about Germany’s colonial past.

In a special session on the last day, Lisabona Rahman, an artist, film critic, archivist, activist, and co-founder of the School of Feminist Thought, openly discussed several sensitive topics.. She highlighted Germany’s complex stance on human rights violations, particularly in relation to Palestine, citing ambivalence rooted in historical burdens. This has led to heightened sensitivity among German authorities towards immigrants, fostering an atmosphere of fear when confronting Germany’s policies.

The current political landscape in Germany reflects a rightward shift, coinciding with public unrest triggered by revelations of a far-right AfD meeting in Wannsee, infamous for Nazi-era atrocities. Lisabona also shared insights into her archival work with the Berlinale Film Festival, underscoring challenges such as language barriers and archival constraints that can impede important discoveries. Additionally, she discussed Germany’s post-World War II cultural initiatives, like Documenta and the Berlinale, aimed at repairing the nation’s image tarnished by Nazi crimes.

In the realm of memorialisation, Lisabona detailed the intricacies of proposing and constructing memorials in Berlin, shedding light on the efforts to commemorate historical injustices and their contemporary relevance.