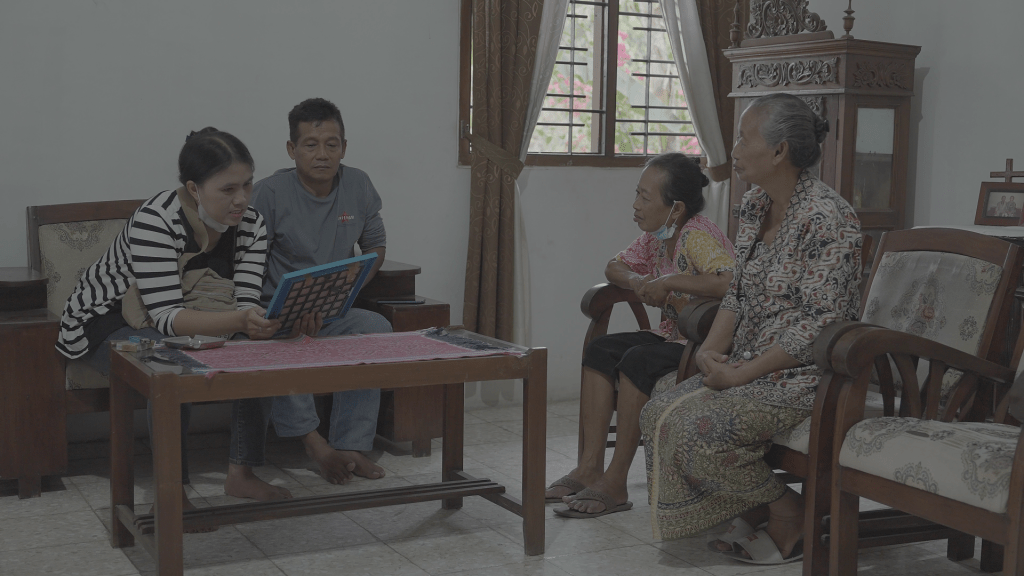

AJAR, in collaboration with filmmaker Manuel Alberto Maia, is proud to announce the production of a full-length documentary exploring the enduring impact of conflict, trauma, and silence across generations in Indonesia, titled Kisah-kisah yang Belum Usai (English title: To An Ending Unwritten). Through intimate stories of resilience and resistance, the film will follow youth in various communities as they break the silence and embark on a journey of intergenerational healing.

“The youth are among the vulnerable groups who bear the consequences of conflict, yet they have been denied the truth of their history,” said Abe, the director of this documentary. “This documentary aims to create a space for honest dialogue, where generations can come together to confront the past and envision a more just future.”

In Bokong Village, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia, young women are at risk of falling victim to human trafficking. A fact that Della, one of the young volunteer working with the local synod and JPIT (East Indonesian Women’s Network) learned quite recently. Working abroad as migrant worker is the dream for Della and friends her age in the village, until she met eye-to-eye with a migrant worker who narrowly escaped from human trafficking and put a touch of reality on her rose colored dream. That until March 2023, over 40 migrant worker corpses have been repatriated to their hometowns in NTT, their dreams of escaping stigma, violence, and hardship vanished. A reality that that often left unspoken from generations above to Della and other youth, to spare her the wounds.

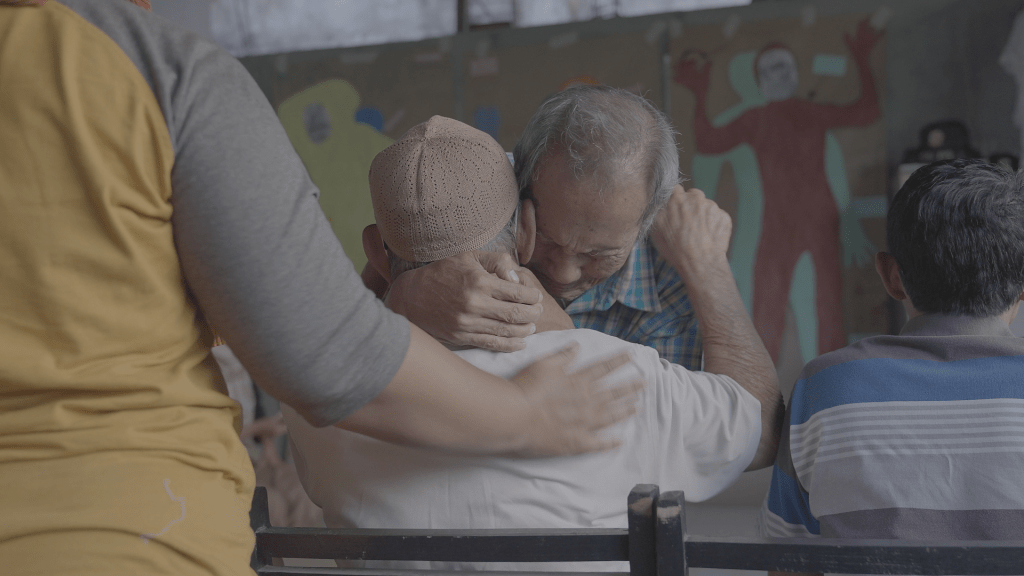

In the hamlet of Buyu Katedo, a 30-minute journey from the heart of Poso Regency, Central Sulawesi, the elderly, witnesses to the massacres of the Poso communal conflict in 2001 that involved a group of Muslim and Christian, also struggle to convey their memories in mere words. For them, witnessing someone’s body being severed and set ablaze defies reason. It seems more plausible to convince themselves that such events never occurred. Brick by painful brick, stories after stories, led by Nurlaela and villagers around, they start to build a memorial to remember the painful past, as well as deconstruct what made such conflict possible at that time, never to let that wounds happened again.

The stigma of being labeled “terrorists” — just because people have different religion, has led to the neglect of the community’s basic rights. Despite being only half an hour away from the heart of the regency, the road to Buyu Katedo is in severe disrepair. The damaged roads and minimal lighting also result in disrupted access to education. Schools often remain closed. The dilapidated roads hinder both teachers and students from attending.

As the adage goes that “… it took a village to raise a child,” in the village of Makarti, South Sulawesi, mothers and families long for their children, born and raised miles away from conflict, to remember their roots. The young children of Timor-Leste descent (then East Timor) refugees have not inherited the knowledge of their birthplace’s culture and language. They are unaware of the circumstances that led them to land in South Sulawesi.

Yet, this history has a lasting impact on them. They face discrimination due to their skin color differing from the locals. Moreover, the history of their parents influences their own socio-economic situation. During the conflict, their parents couldn’t pursue education, leading to difficulties in finding jobs and living in poverty, affecting the family’s financial condition.

In a parallel turn of events, closer to the border between Indonesia and Timor-Leste, the second and third-generation children of East Timor refugees live without a clear residential status in East Nusa Tenggara. Their parents once fled to Indonesia with hopes of a peaceful and prosperous life. But now, their children are being further impoverished by the state.

For 24 years since the conflict, they still reside in refugee camps. Currently, they face the threat of relocation to unproductive lands far from livelihood sources. Egydio, a second-generation refugee in Desa Tuapukan, is resisting the injustices faced by the refugees. He and other young people take to the streets, demanding their rights to a place to live is not limited to land or a house; it also involves access to a dignified livelihood. “If we stay silent, we will be blamed by future generations,” Egydio asserted. They learned to organise themselves by establishing Sekolah Rakyat, ‘school for the people’.

Indonesia bears a long history of violence, and perhaps what befell them in those places started in 1965, the beginning of when the state learned that violence is viable answer against differences. In Yogyakarta, the survivors of the country-wide 1965-1966 human rights violations have aged, and many have passed away. Simbah Martini’s relatives, children also face discrimination after her release from prison in 1971, being branded as ‘communist’. They struggle to access higher education or find employment. Their relationship with their victimized parents becomes strained. These children, in turn, stigmatize their own parents, considering them as troublemakers. But the older generations, including Martini, still can speak, and only by speaking the truth, they can heal the wounds left.

Speaking allows them to acknowledge the lasting impact of conflicts, which doesn’t end with the events themselves but continues to linger to this day. Conflicts trigger trauma and attach stigmas. They lead to various forms of structural marginalization within society. Though the locations of these people differ, each with its distinct conflict background, there is a common thread that links them all — this thread is the severed transmission of historical information from the elder generation to the young. Yet, the youth are among the vulnerable groups who bear the consequences. Generations have become accustomed to silence.

And gradually, in these five locations, as the youth embark on a journey to understand their life history, their voices open possibilities. We are glad to announce that production has commenced to create a full length documentary that tells their stories, primarily the ones in Yogyakarta and Kupang

The documentary is expected to be completed in 2024, alongside an impact program designed to:

- Facilitate community-based screenings and discussions.

- Develop educational resources for schools and youth groups.

- Support initiatives for intergenerational healing and reconciliation.

We invite you to join us on this journey of truth-telling and transformation.

Stay tuned for updates and opportunities to get involved.